Reflection on the Stories-in-Motion WS Spring/Summer 2021

I am an urban researcher from Germany. I studied urban planning and storytelling was a marginalized topic. Therefore, when I started to explore storytelling as a participatory method in urban planning, I first needed to comprehend the meaning and functions of storytelling itself. That is why I reach out to the StoryCenter. Mainly to better understand what constitutes a story and how storytelling works, but also to learn the technique of storytelling myself. During this process, I gained more knowledge about the relationship between stories and space and became curious about how storytelling helps us capture, experience, and interact with different places in the world. One way to work with stories and space is through story mapping. The Stories-in-Motion workshop (SiM-Workshop), one of the most recent additions to the StoryCenter program, incorporates the story mapping method, connecting my research interests to the work of the StoryCenter. I participated in the first official Stories-in-Motion workshop in spring 2021 and was fortunate to get a Fulbright scholarship that allowed me to Berkeley in the summer of 2021 to conduct research in the Bay Area. I now want to share with readers of this blog what I learned from attending the workshop and what the other participants experienced.

Besides “narrative atlas” or georeferenced storytelling, “story map” is one of the terms that characterize the growing interest in the relationship between maps and narratives (Caquard 2013: 137). This interest is evident in many papers and blogs that present and discuss maps that appear in various narrative forms. The new trend is especially evident in new story mapping tools by ArcGIS and google maps. Esri (AcGIS) designed a new tool for creating georeferenced story maps. The tool offers a predesigned choice of templates for tours, cascades, journals, series or shortlists where everyone can create an individualistic story map. “ArcGIS Story Maps let you combine authoritative maps with text, images, and multimedia content, and make it easy to harness the power of maps and geography to tell your story. Story Maps can be used for a wide variety of purposes; for advocacy and outreach, virtual tours, travelogues, delivering public information, and many more.” (Szukalski, B.; Carroll, A. (2020).

However, it is not necessarily easy for everyone to tell and portray a story, let alone mapping. Questions that arise: How to write a story? What contains a story? How to be aware of your own voice? How to handle all the elements of a story map? Who will be your audience? And how does georeferenced mapping work?

These questions lead to a powerful story that not only contains a narrator, but also an audience. To create those stories we need spaces for listening and sharing. As the pandemic started, the StoryCenter began to offer workshops online to provide individuals and organizations with skills and tools that support self-expression, creative practice, and community building. Although one important part of storytelling is the emotional and personal exchange of stories, it was still possible to create a safe space online, where people from all over world could work on their digital stories and story maps and share them.

Such a safe space could be realized in the SiM-Workshop. The workshop focused on the integration of mobile documentary media production with Geographical Information System. Interactively the participants learned how to use their mobile devices to produce powerful and effective digital stories and connect them with maps. The workshop took place online during May to July 2021 every Wednesday from 10am to 12pm, with 21 participants from the US, Canada and Europe. The goal is for people to create digital stories (images, videos, audios) that they connect to georeferenced points on a map in the ArcGIS StoryMap tool.

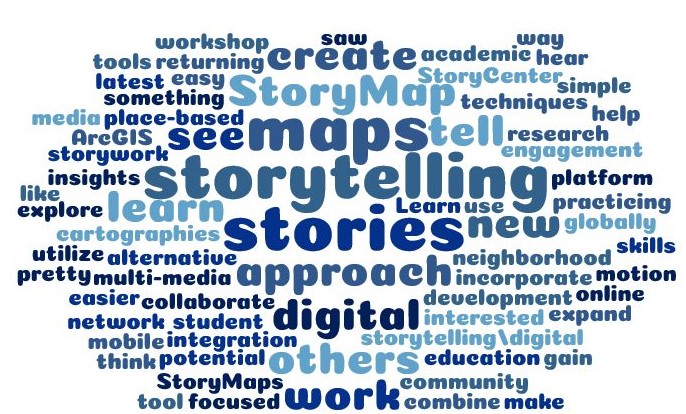

Through this workshop, we learned more about the connection people make between stories and maps, about the process of story mapping, but also about using a new technology and creating trust and safe space through digital communication tools. Below we would like to reflect on these insights. We conducted a survey with the participants about their experience in the workshop. We asked them why they participated in the workshops. The answers are represented in a word cloud.

Wordcloud from the participants’ answers

I would like to talk about this in more detail by discussing storytelling and the “task of stories” (Lambert/Hessler 2018: 13) as a deeply rooted part of human life and relating it to the experiences of the participants in the workshop. To begin with, I address the importance of stories and storytelling for human beings and then story mapping as a process.

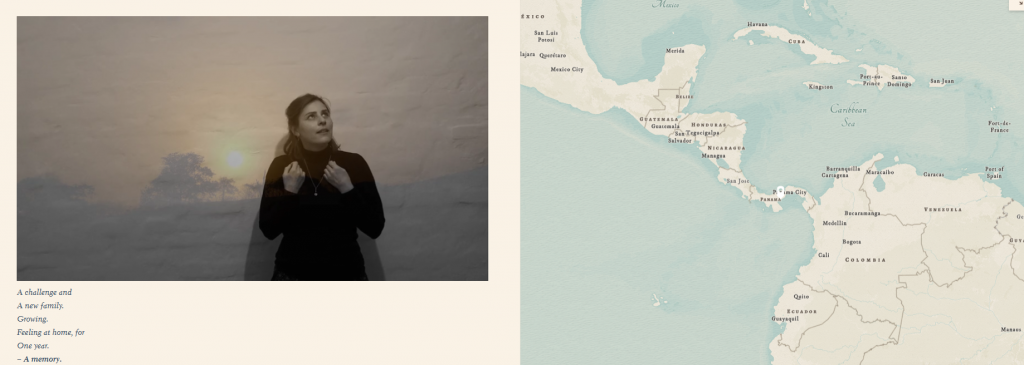

First, the meaning of storytelling for people is profound. People´s identities are defined by their stories. As humans, we perceive historical and current events by connecting the past to the present through storytelling. Telling someone about our experience gives meaning to our perspective, so we shape who we are through the stories we tell about ourselves. (Moenandar/Wood 2017: xii). The act of storytelling, where the narrator takes responsibility for events, that conveys feelings and thoughts that would otherwise be inaccessible, makes it an act of empowerment. The use of storytelling, then, is anything but abstract: given its inherent and universal ability to convey “strategies for coping with situations,” storytelling is, according to Burke (1973: 293), an “instrument for living.” Showing this, one participant reveals his or her thoughts about this in the survey: “Because of the multi-media I was able to incorporate, I uncovered a new piece of my story. This new information showed me my self-esteem was deeply affected after my best friend dumped me when I was a young girl. Transforming that moment into a video, of my friend literally disappearing from my life, was an unexpected healing for me.” (Quote Survey).

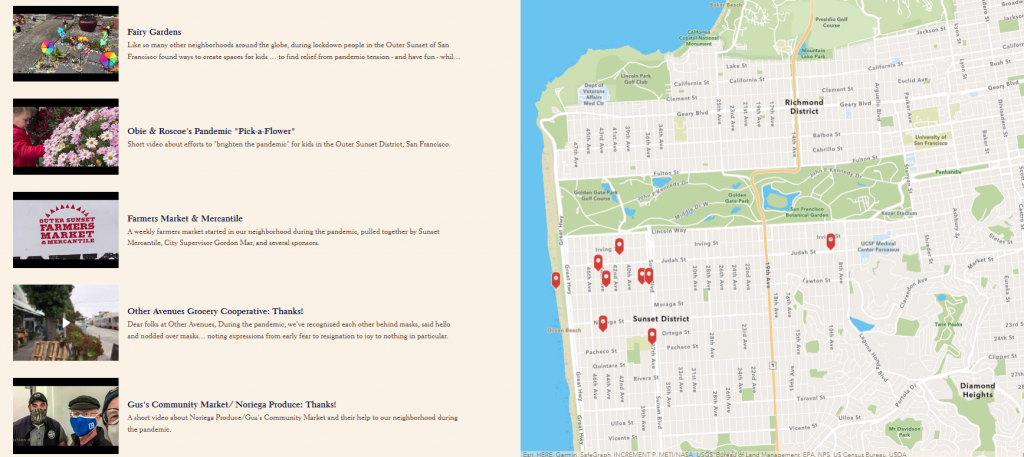

Moreover, the fact that there is the term Homo Narrans makes clear how much storytelling shapes the human communication paradigm. Humans develop narratives as a means of making sense of the world (Deuten/Rip 2000: 136). A process that one SiM-Workshop participant reflected on: “I love my neighborhood and found myself taking pictures and shooting short videos to document different aspects. The opportunity to turn it into something more coherent is what inspired me to take the workshop.” (Quote Survey). However, storytelling is also “the way people share ideas and meaning.” (Chancellor, Lee 2016: 39): “My neighbors’ and neighborhood’s experiences through the pandemic, supporting each other, are important to me. I focused on locations/people locally that/who were bright spots during the pandemic.” (Quote Survey). Thus, on the one hand, stories serve to understand and order our world (Ricoeur 1986); on the other hand, they also reflect the subjective perceptions of the storyteller. Both mean that personal stories convey information about the narrator’s view of his environment, in this case their neighborhoods.

Second, understanding story mapping as a process contains a closer a look at the meanings of maps and their connection to stories. Just like stories, maps help people understand the world they live in. Maps also influence the way they see and understand the world. Maps can have real impacts on the people in the area they depict because every map tells a story by itself. Stories of past lives, of mineral resources, of ancient walls, stories of wars and border crossings, stories of values.

Connecting stories and maps is a complex process. It involves an effort to understand the world as a landscape made up of relationships – relationships between places and sociological, cultural aspects and values that shape us. Through the survey, I learned about new discoveries participants made during the process:

“I spent a lot of time in the park gathering information for the video, and thinking about the qualities of the park helped me appreciate the open spaces in our neighborhood.” (Survey quote).

“I learned more about a geography I already knew. I was forced to interact with space again and […] had to look at it in a more reflexive way.” (Survey quote).

The process of story mapping also shows how working with stories in conjunction with maps helps changing perceptions, “I realized what a small town I live in. Culturally and geographically.” (survey quote). The workshop is more than just locating a story to a map, it is a process for the participant’s that might change their sense of belonging: “[The workshop] made me really appreciate the people in my neighborhood, because we all survived the crisis – until now. Especially the neighbors closest to us, on our block.” (Survey quote).

Story mapping as a means of communicating allows people to share their perspectives and personal experiences with others. Related to broader issues story maps can be very powerful, especially if they have a deep connection to space. “I normally try to be “deep” “insightful” “analytical” but this time, I just let the love for this place guide me and it was delightful.” (Quote Survey). The results were story maps, consisting of digital stories as poems, written and spoken words, images, videos and georeferenced current or historical maps with different layers. As one participant summarized: “The map became the backdrop for the story.” (Quote Survey)

Literature

Bamberg, M.; Georgakopoulou, A. (2008): Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. In: Text & Talk 28, 3, 1. doi: 10.1515/TEXT.2008.018.

Caquard, S. (2013). Cartography I: Mapping narrative cartography. Progress in Human Geography, 37(1), 135-144.

Chancellor, R., & Lee, S. (2016). Storytelling, oral history, and building the library community. Storytelling, Self, Society, 12(1), 39-54.

Lambert, J.; Hessler, B. (2018): Digital Storytelling. Capturing Lives, Creating Community. Milton.

Moenandar, S.-J.; Wood, L. (2017): Stories of Becoming. Using storytelling for research, counselling and education. Nijmegen.

Ricoeur, P. (1986): Life. A Story in Search of a Narrator. In: Doeser, M.C.; Kraay, J.N. (Hrsg.): Facts and Values. Dordrecht, 425-437. = 19.

Szukalski, B.; Carroll, A. (2020): The Myriad Uses of StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1b38cf02f39849478d3123dcd9465022

Further Reading

Eckstein, B.J.; Throgmorton, J.A. (2003): Story and Sustainability. Planning, Practice, and Possibility for American Cities.

Finnegan, R.H. (2004): Tales of the city. A study of narrative and urban life. Cambridge.

Sandercock, L.; Attili, G. (Hrsg.) (2010): Multimedia Explorations in Urban Policy and Planning. Beyond the flatlands. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York.

Hanna Seydel, 08/26/2021